Do Bondo Apes Really Exist?

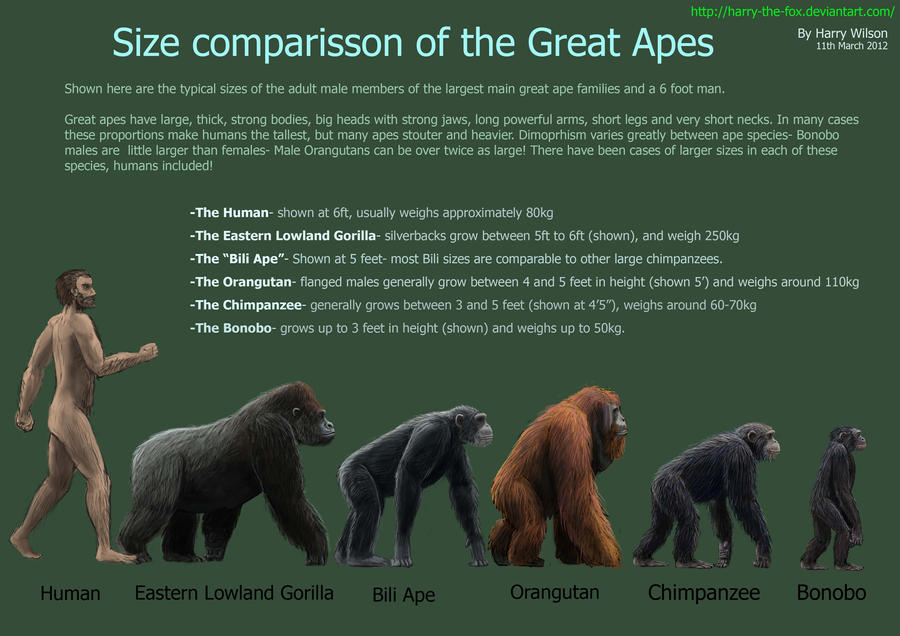

Deep within the dense jungles of the Democratic Republic of Congo lies the legend of the Bondo apes, also called Bili apes. These creatures, rumored to be a cross between chimpanzees and gorillas, were said to possess extraordinary abilities such as killing lions and surviving poisoned arrows.

The remote and war-torn region where they allegedly reside, known as the Bili Forest, has made it challenging for scientists to confirm or debunk these legends.

The Myth of Bondo / Bili Apes

Tales of the Bondo apes began to take shape in the remote villages surrounding the Bili Forest, where stories of giant, lion-killing apes were passed down through generations. These accounts, often shared around campfires or whispered in hushed tones, spoke of creatures so powerful that they could challenge even the fiercest predators of the jungle.

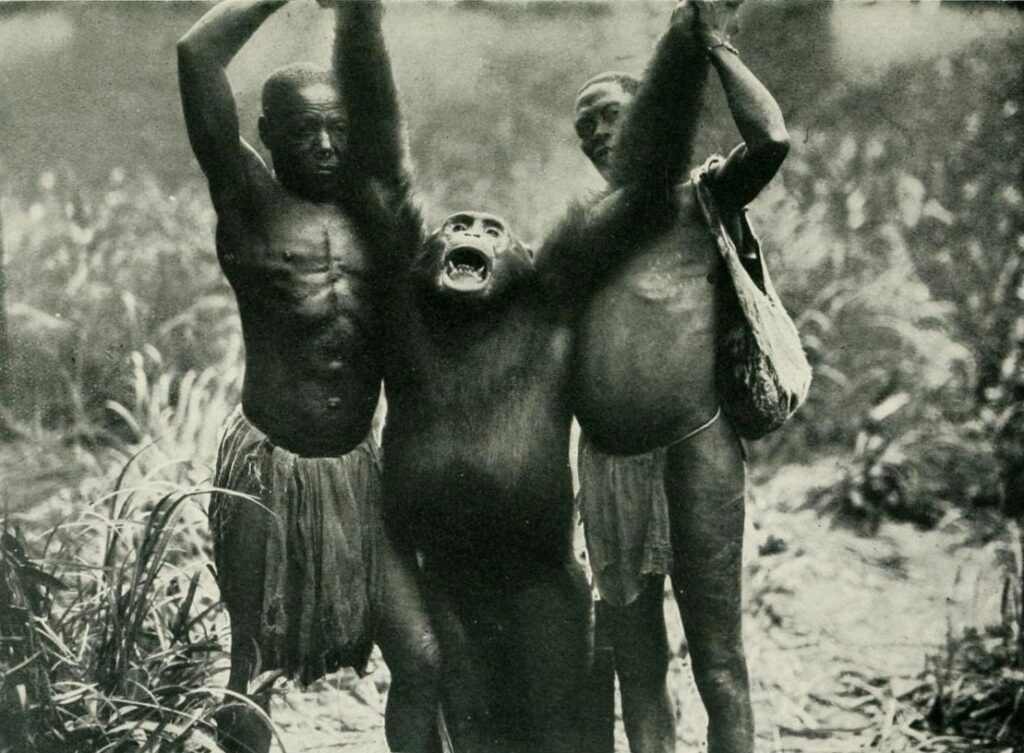

The myth gained momentum as occasional sightings and encounters with unusually large chimpanzees fueled speculation among hunters and villagers. Reports of footprints larger than those of gorillas, fecal droppings three times the size of typical chimp dung, and photographs depicting massive apes captured the imagination of both locals and outsiders.

One Centuriy Old Mystery

In 1898, a Belgian army officer returned from the depths of what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, carrying with him gorilla skulls procured from the dense forests near Bili village, nestled along the Uele River in the northern reaches of Congo’s Bondo region. Strikingly, no other gorilla sightings had been reported within hundreds of miles of Bili, then or since.

These skulls found their way to Belgium’s Congo Museum in Tervueren, where curator Henri Schouteden meticulously examined them. Noteworthy for their anatomical deviations from known gorilla specimens and their unique geographical origin – situated midway between the farthest extents of western and eastern gorilla populations – Schouteden classified them as a distinct subspecies, Gorilla gorilla uellensis.

However, this classification faced skepticism from mammalogist Prof. Colin Groves. In 1970, Groves contested the separate taxonomic status of the Bili ape, asserting that the skulls were identical to those of western lowland gorillas. Consequently, the Bili ape slipped into relative anonymity.

It was against this backdrop of folklore and mystery that Swiss-Kenyan photographer Karl Ammann stumbled upon the skull in 1996.

The Quest for the Bondo Apes

Ammann’s subsequent expeditions into the heart of the Congo jungle further fueled the mystique surrounding these enigmatic creatures. The myth gained traction, with some suggesting the Bondo apes as a new species or a hybrid between chimps and gorillas. The allure of discovering a “missing link” in the primate world added an element of excitement and intrigue to the quest for answers.

However, as scientific investigations progressed, the myth began to unravel. Genetic analyses, behavioral observations, and ecological studies gradually dispelled the notion of Bondo apes as a distinct species or mythical creatures.

A team of scientists embarked on a daring quest to uncover the truth behind the legendary Bondo apes. Among these researchers was Cleve Hicks from the University of Amsterdam, whose journey into the depths of the Congo jungle would shed light on the existence of these elusive creatures.

Bili Chimps

The journey into the heart of the Congo’s Bili Forest uncovered the truth behind the Bondo apes myth.

One of the most striking revelations was the discovery of a distinct chimpanzee culture flourishing within the dense foliage of the Bili Forest. Unlike their counterparts in other parts of Africa, the Bili chimps exhibited behaviors and traditions that set them apart as a unique population.

Central to this newfound culture was the phenomenon of ground nests, a behavior rarely observed in chimpanzee communities elsewhere. While chimpanzees are known to construct nests in the safety of treetops, the Bili chimps showed a preference for the forest floor.

The presence of these ground nests, meticulously woven from interlaced branches and foliage, challenged existing notions about chimpanzee behavior and raised intriguing questions about the factors driving this adaptation. Despite the inherent risks posed by predators such as lions, leopards, and other dangerous fauna, the Bili chimps seemed unfazed as they nestled in their ground-level abodes.

The Significance of Ground Nests

Cleve Hicks, during his extensive fieldwork, documented numerous instances of these ground nests, observing their large size and sturdy construction. This behavior, initially puzzling to researchers, hinted at a complex interplay between ecological pressures, social dynamics, and adaptive strategies unique to the Bili chimpanzees.

The significance of the ground nests extended beyond mere shelter; it provided a window into the resilience and ingenuity of these primates in navigating their challenging environment. By embracing ground-level nesting, the Bili chimps demonstrated a capacity to coexist with potential threats while carving out a distinctive niche within their ecosystem.

Moreover, the ground nests are a demonstration of chimpanzee cultures, showcasing the diversity and complexity inherent in these intelligent beings. While the reasons behind this behavior are still subject to ongoing study and debate, it underscores the need for continued exploration and understanding of primate societies in their natural habitats.

Unusual Chimpanzees

Unlike their counterparts in other regions, the Bili chimpanzees showcased a different diet and cultural repertoire. Their preference for nesting on the ground, akin to gorillas, and their adept use of exceptionally long tools for foraging highlighted their adaptability and resourcefulness in the challenging jungle environment.

Upon encountering these primates, Hicks noted a distinct demeanor—an air of authority and confidence that spoke volumes about their unfamiliarity with human presence and potential threats. Far removed from human settlements and hunting pressures, these chimps exhibited curiosity rather than fear, embodying a sense of ownership over their domain.

Moreover, Hicks’ findings shattered previous population estimates, revealing that the Bili region harbored a significant population of wild chimpanzees, perhaps the largest known in the world. Some individuals resided in such remote areas that they had likely never encountered humans or experienced the perils of hunting.

Tools and Diet

Bili chimpanzees demonstrate a keen sense of tool selection, employing varying lengths and types for different tasks. For the formidable driver ants, they wield long, thick sticks exceeding 2 meters in length, allowing them to probe deep into the ants’ cavernous mounds while maintaining a safe distance from the swarming masses.

In contrast, when dealing with ponerine ants, known for their excruciating stings, the chimpanzees opt for short, sturdy sticks to disable their defensive capabilities before consumption.

The utilization of stout digging sticks to access subterranean beehives for honey and delicate wands to prey on non-swarming ants further exemplifies their tool-making prowess. These tools not only facilitate food gathering but also hint at the complex cognitive processes at play in their daily lives.

Diet

The dietary preferences of Bili chimpanzees diverge significantly from other chimpanzee populations. They exhibit a particular fondness for cracking open termite mounds made by specific species, such as Cubitermes and Thoracotermes macrothorax, using substrates. This selective foraging behavior contrasts with their indifference towards Macrotermes termite mounds, a preferred delicacy for many other chimpanzee groups.

The concept of culture emerges as a crucial lens through which to understand these dietary choices. While Macrotermes termites are abundant in the region, the Bili chimpanzees seem to lack a tradition of consuming them, highlighting cultural transmission of behaviors within the group. This nuanced relationship between available resources and cultural practices underscores the complexity of chimpanzee societies and their adaptive strategies.

Additionally, the Bili chimpanzees’ hunting or scavenging behaviors, targeting various animals including African giant snails, tortoises, pangolins, and even leopards, reveal their versatile dietary repertoire. These observations challenge traditional notions of chimpanzee diets and behaviors, showcasing the diverse strategies employed by these primates to thrive in their environment.